https://nzareblog.wordpress.com/2020/11/03/positive-leadership/

NZARE post on leadership, discussing high well-being of teachers and low well-being of teachers.

“Teachers are the most precious resource that we have in our education system, but too often we fail to treat them as ‘taonga’ [treasures] but as a means to an end.” (Cameron et al., 2007)

1. The importance of teachers feeling that they are valued

Teachers all talked about the importance of appreciation, recognition, and feeling valued in contributing to their wellbeing. High wellbeing teachers were more likely to comment positively about this, for example leaders’ listening to their views:

“I think they listen to teacher voice, and I think they do value it” (Teacher D).

The same teacher commented on the effects of a lack of recognition in a previous school:

“I kind of really worked hard to make it a wonderful department, we got brilliant results for our students, but still I didn’t get any promotion within that school, and that was a little bit disheartening” (Teacher D).

2. The impact of meaningful professional development

All teachers referred to the potential for professional development to positively impact their wellbeing, with many discussing the sense of achievement they experienced through their own personal and professional growth.

“[The leaders are] really challenging us with that reflective… being reflective on our own practice, you know, that’s stuff’s good” (Teacher C).

However, low wellbeing teachers more frequently expressed a lack of understanding of the content of professional development, or the rationale behind it:

“We are encouraged to just kind of take it step by step, but I don’t know if I fully understand the concepts?” (Teacher B).

3. Enabling teacher agency in decision making and changes

There were clear differences between the low wellbeing and high wellbeing teachers in terms of the degree of agency that they felt in decision making and changes occurring in the school. High wellbeing teachers were confident to approach leaders to ask questions and felt they were listened to:

“We feel part of the solution rather than just being, you know, symbols of the problem.” (Teacher C)

However, low wellbeing teachers more commonly expressed that their views were not taken into account, and they disagreed with the changes occurring in the school:

“Too much change and not seeing the reasons for change. Or it could be someone’s reason for change, but the evidence doesn’t back that up” (Teacher E).

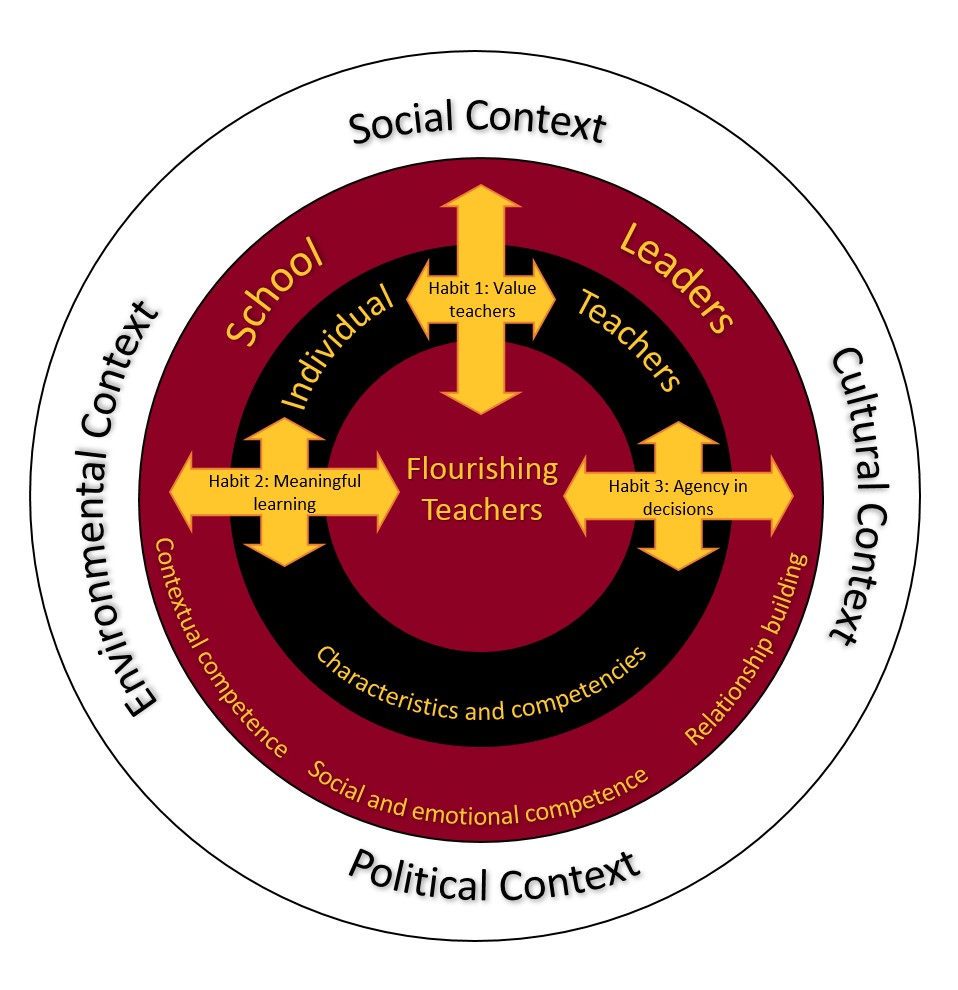

Flourishing teachers are placed at the centre of the model, with the surrounding circles and arrows indicating the factors that enable teacher to flourish.

The next level is the individual teachers, and their characteristics and competencies – for example, a teacher’s level of optimism, or coping skills can influence their wellbeing.

The next level are school leaders, and three areas that influence their interactions with teachers: contextual competence (a leader’s ability to understand and respond to context), social and emotional competence, and relationship building.

The outer circle represents contexts that are often outside of teachers or leader’s direct control, for example political context can refer to educational policy.

The three arrows in the model represent leadership habits (actions repeated regularly over time) that can positively influence teachers’ wellbeing:

- ensuring teachers feel that they are valued,

- providing meaningful professional development, and

- enabling teacher agency in decision making and changes.

The three habits are shown interacting with both leaders and teacher’s characteristics and competencies – for example school leaders’ skills in areas such as relationship building, affect the degree to which they are able to successfully enact the habits that can improve teacher wellbeing, and what makes professional development meaningful to a teacher will depend on their existing skills and their own needs.

Comments

Post a Comment